There seems to be a lot of fighting and arguing over the future of C++.

On Reddit and a certain orange website, definitely, but also surely at the official C++ standard committee meetings. You don’t need to look very far.

EDIT (25-11-2024): Typos and phrasing. Mentioned on HN, r/cpp, lobste.rs.

The Absolute State (of C++)

It looks like we’re in the following situation:

-

C++’s Evolution Working Group (EWG) just

achieved consensus

on adopting

P3466 R0 - (Re)affirm design principles for future C++ evolution:

- This means no ABI breaks, retain link compatibility with C and previous C++.

- It also means no ‘viral annotations’ (no lifetime annotations, for example).1

- It doubles down on a set of incompatible goals, ie. no ABI break and the zero-overhead-principle.2

- Whether this is good or bad, it is a (literal) doubling down on the current trajectory of the C++ language.

In the meantime:

-

The US government wants people to stop using C++:

- The CISA

- The NSA

- The White House, apparently.

- No, really. Various branches of the US government have released papers, reports, recommendation to warn the industry against usage of memory-unsafe languages.

-

All sorts of big tech players are adopting Rust:

- Microsoft is apparently rewriting core-libraries in Rust.

- Google seems to be committing to Rust, and in fact started working on a bidirectional C++/Rust interop tool.

- AWS is using Rust.

- etc.

- Speaking of big tech, did you notice that Herb Sutter is leaving Microsoft, and that it seems like MSVC is slow to implement C++23 features, and asking the community for prioritization.

- The infamous Prague ABI-vote happened (tl;dr: “C++23 will not break ABI, it’s unclear if it ever will.”), Google supposedly significantly lowered its participation in the C++ development process, and instead started to work on their own C++ successor language. They even have a summary outlining all of the issues they had trying to improve C++.3

- Stories of people trying their best to participate in the C++-standard committee process across multiple years, only to be chewed up and spit out are widely known and shared throughout the community. (A feature landing in C first doesn’t help either.)

-

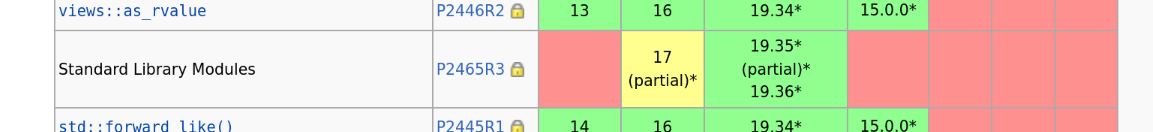

Modules are still not implemented.

Are we modules yet?4

- ‘Safety Profiles’ are still in a weird state with no existing implementation, trying to retrofit some amount of safety onto existing C++ code while minimizing changes to existing code. Sean Baxter himself took a stance against profiles, and described C++ as “underspecified”.

- You can find a lot more sources if you keep digging, see for example this report / analysis a reader wrote and shared with me.

I don’t know about you, but if I were to look at all of this as an outsider, it sure would look as if C++ is basically falling apart, and as if a vast amount of people lost faith in the ability of C++’s committee to somehow stay on top of this.5

Two Cultures

People seem to be looking for other solutions.

Say, Google. Google evidently lost faith in ’the process’ ever since the ABI-vote. This isn’t a loss of faith in the language itself, Google has one of the largest C++ codebases in the world, and it has served them incredibly well. It’s a loss of faith in the language’s ability to evolve as pressure mounts from different angles (potential government regulations, competing languages, a desire for better performance and safety guarantees from key players, etc.).

So what’s the problem? Why doesn’t C++ just…change?

Well, figuring that out is easy. Just look at what Herb Sutter said in his paper on profiles:

“We must minimize the need to change existing code. For adoption in existing code, decades of experience has consistently shown that most customers with large code bases cannot and will not change even 1% of their lines of code in order to satisfy strictness rules, not even for safety reasons unless regulatory requirements compel them to do so.”

– Herb Sutter

Cool. Is anyone surprised by this? I don’t think so.

Now, let’s contrast this with Chandler Carruth’s biography on the WG21 member page:

I led the design of C++ tooling and automated refactoring systems built on top of Clang and now part of the Clang project. […]

Within Google, I led the effort to scale the automated Clang-based refactoring tools up to our entire codebase, over 100 million lines of C++ code. We can analyze and apply refactorings across the entire codebase in 20 minutes.

Oh. Do you see it? (Yes you do, I highlighted it.)

It’s “automated tooling”. Except it’s not just that, automated migration tooling is just the peak, the single brightly glowing example.

We’re basically seeing a conflict between two starkly different camps of C++-users:

- Relatively modern, capable tech corporations that understand that their code is an asset. (This isn’t strictly big tech. Any sane greenfield C++ startup will also fall into this category.)

- Everyone else. Every ancient corporation where people are still fighting over how to indent their code, and some young engineer is begging management to allow him to set up a linter.

One of these groups will be capable of handling a migration somewhat gracefully, and it’s the group that is capable of building their C++ stack from versioned source, not the group that still uses ancient pre-built libraries from 1998.

This ability, to build the entire entire dependency stack from versioned source (preferably with automated tests) is probably the most critical dividing line between the two camps.

In practice, of course, this is a gradient. I can only imagine how much sweat, tears, bills and blood must’ve flown to turn big tech codebases from terrifying balls of mud into semi-manageable, buildable, linted, properly versioned, slightly-less-terrifying balls of mud.

With the bias of hindsight, it’s easy to think of all of this as inevitable: There was a clear disconnect between the needs of corporations such as Google (who use relatively modern C++, have automated tooling and testing, and modern infrastructure), and the (very strong) desire for backwards compatibility.

To go out on a limb, the notion of a single, dialect-free and unified C++ seems like it’s been dead for years.6 We have, at the very least, two major flavors of C++:

-

Any remotely modern C++. Everything can be built from versioned source using some sort of

dedicated, clean and unified build process that’s at least slightly more sophisticated than raw CMake,

and sort of looks like it just works if you squint a little. Some sort of static analyzers, formatter,

linter. Any sort of agreement that keeping a codebase clean and modern is worthwhile. Probably

at least C++17, with

uniqe_ptr,constexpr, lambdas,optional, but that’s not the point. What matters is the tooling. - Legacy C++. Anything that’s not that. Any C++ that’s been sitting in ancient, dusted-up servers of a medium-sized bank. Any C++ that relies on some utterly ancient chunk of compiled code, whose source has been lost, and whose original authors are unreachable. Any C++ that sits deployed on pet-type servers, to the point that spinning it up anywhere else would take an engineer a full month just to figure out all of the implicit dependencies, configs, and environment variables. Any codebase which is primarily classified as a cost-center. Any code where building any used binary from source requires more than a few button presses, or is straight-up impossible.

You’ll notice that the main difference isn’t about C++ itself at all. The difference is tooling and the ability to build from versioned source in any clean, well-defined manner. Ideally, even the ability to deploy without needing to remember that one flag or environment variable the previous guy usually set to keep everything from imploding.

How much of eg. Google’s codebase is following ‘modern’ C++ idioms is pretty much secondary to whether the tooling is good, and whether it can be built from source.

A lot of people will tell you that tooling isn’t the responsibility of the C++ standard committee, and they are right. Tooling isn’t the responsibility of the C++ standard committee, because the C++ standard committee abdicates any responsibility for it (it focuses on specifications for the C++ language, not on concrete implementations)7. This is by design, and it’s hard to blame them considering the legacy baggage. C++ is a standard unifying different implementations.

That said, if there’s one thing which Go got right, it’s that tooling matters. C++, in comparison, is from a prehistoric age before linters were invented. C++ has no unified build system, it has nothing even close to a unified package management system, it is incredibly hard to parse and analyze (this is terrible for tooling), and is fighting a horrifying uphill battle against Hyrum’s Law for every change that needs to be made.

There’s a massive, growing rift between those two factions (good tooling, can effortlessly build from source vs. poor tooling, can’t build from source), and I honestly don’t see it closing anytime soon.

The C++ committee seems pretty committed (committeed, if you will) to maintaining backwards compatibility, no matter the cost.

I don’t necessary disagree with this, by the way! Backwards compatibility is a huge deal for a lot of people, for very good reasons. Other people don’t care nearly as much. It doesn’t matter which group is “right”: It’s just that these are incompatible views.

Consequences

This is why profiles are the way they are: Safety Profiles are not intended to solve the problems of modern, tech-savvy C++ corporations. They’re intended to bring improvements without requiring any changes to old code.

Likewise, modules. You’re intended to be able to “just” import a header file as a module, and there should not be any sort of backwards compatibility issues.

Of course, everyone loves features which can just be dropped-in and bring improvements without requiring any changes to old code. But it’s pretty clear that these features are designed (first and foremost) with the goal of ’legacy C++’ in mind. Any feature that would require a migration from legacy C++ is a non-starter for the C++ committee since, as Herb Sutter said, you essentially cannot expect people to migrate.

(Again, building features with ’legacy C++’ in mind is not bad. It’s a completely sensible decision. )

This is something which I try to keep in mind when I look at C++ papers: There’s two large audiences here. One is that of modern C++, the other is that of legacy C++. These two camps disagree fiercely, and many papers are written with the needs of one specific group in mind.

This, obviously, leads to a lot of people talking past each other: Despite what people think, Safety Profiles and Safe C++ are trying to solve completely different problems, for different audiences, not the same ones.

The C++-committee is trying to keep this rift from widening. That’s, presumably, why anything in the direction of Safe C++ by Sean Baxter is a non-starter for them. This is a radical, sweeping change that could create a fundamentally new way of writing C++.

Of course, there’s also the question of whether specific C++ standard committee members are just being very, very stubborn, and grasping at straws to prevent an evolution which they personally aesthetically disagree with.

Far be it from me to accuse anyone, but it wouldn’t be the first time I heard that the C++ committee applied double standards such as: “We expect a full, working implementation across several working compilers from you if you’d like to see this proposal approved, but we’re still happy to commit to certain vast projects (eg. modules, profiles) that have no functioning proof of concept implementation.”

If this were the case (I genuinely cannot say) then I really wouldn’t know for how much longer C++ could continue going down that road without a much more dramatic split.

And all of that that is not even getting into the massive can of worms and problems that’d be caused by breaking ABI compatibility.